What

follows is not an essay plan but some notes with information and

ideas that might be useful in working out an essay plan.

Introduction

– this title concerns two separate but connected topics, nuclear

armaments and the development of nuclear power for peaceful

purposes. It is also related to the dangers posed by other Weapons of

Mass Destruction (WMDs).

Nuclear

arms – some information

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-33521655

There

are currently 9 nuclear powers – the US (since 1945), the Russian

Federation (1949), the UK (1952), France (1960), China (1964), Israel

(1967?) , which now also has a submarine with nuclear arms and thus a

second strike capability (2003), India (1974), Pakistan (declared

1998, probably developed from the 1970s), North Korea (2003).

Apartheid South Africa had them and then eliminated them (1982-94).

Canada deploys US missiles but has no independent control of them.

Germany, Italy, Holland and Belgium and Turkey have US nuclear bases

and are part of NATO's nuclear

sharing

policy

https://eu.boell.org/en/2016/05/25/european-union-and-nuclear-disarmament-sensitive-question

which

means they take

common decisions with the US on nuclear weapons policy and maintain

technical equipment required for the use of nuclear weapons.

Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine had them after the break-up of the

Soviet Union but returned them to the Russians almost

immediately.

The

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968) came into force in 1970.

There was also the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (1963) and the

Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (1998)

There

are treaties concerning other potential Weapons of Mass Destruction

(WMDs). These include the banning of Chemical weapons (1992),

Biological weapons (1971) and Weapons in Outer Space (1967).

The

Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is responsible

for monitoring

the development of nuclear power for peaceful

purposes (the

production of energy for domestic and industrial consumption) and

ensuring that nuclear materials and equipment are safe and not

diverted from legitimate peaceful purposes to military

purposes.

(There is a similar Agency in the Hague for chemical products and the

potential for producing chemical weapons.) The dispute, sanctions,

recent deal between the UN and Iran (July 2015), and the recent US

withdrawal from the deal May 2018), and the continuing support for,

doubts about and criticism of the deal, demonstrate the difficulty of

this

task.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran_nuclear_deal_framework

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/18/opinion/a-safer-world-thanks-to-the-iran-deal.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/world/middleeast/iran-sanctions-lifted-nuclear-deal.html

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iran/

https://edition.cnn.com/2019/12/11/politics/pompeo-iran-sanctions/index.html

Nuclear

weapons

They

are clearly expensive to built, maintain and update.

Are

they dangerous? Are they weapons that are likely to be used? Probably

not in terms of whether states really intend to use them one day,

although tensions between the US and North Korea at the start of the

Trump administration were cause for concern. There are also worries

that various other countries may try to develop weapons. Moreover,

there is always the danger of an accident due to a technological or

human error, and the threat of a decision taken by a madman. There

is, in the case of India and Pakistan (as in the similar but slightly

different case of the US and USSR during the Cuban crisis), the

danger of escalation from a conventional conflict to a nuclear war in

the Kashmir region. In addition, poorer countries may spend too

little on maintenance and security systems (e.g. the 2-key launch

system or Russia's security failures during and after the collapse of

the Warsaw Pact and Soviet Union, 1989-91). Other experts claim that

a new arms race combined with the abandoning of international

treaties and greater automation and digital complexity of

nuclear-arsenals makes the world less and less secure.

So

there is a good argument for trying to abolish them completely.

However,

an attack by a nuclear power on another nuclear power, or the ally of

a nuclear power,

would be suicidal

(the Mad Doctrine of the Cold War). For example, an attack by a

future Iran hypothetically in possession of nuclear weapons could

destroy Israel but Israel would retaliate and destroy Iran. An attack

on a non-nuclear power would lead to international isolation, if not

a coordinated counter-attack from the global community or other

nuclear powers (e.g. North Korea on South Korea). So

the real danger may be that nuclear weapons or materials could fall

into the hands of terrorists or be targeted by terrorist attacks (in

Pakistan, for instance).

http://www.nci.org/nci-nt.htm

There

is also the question of what would happen to the nuclear weapons in

the event of a civil war in a state which has nuclear arms. This is a

real danger in Pakistan and was one of the major international

concerns during the break-up of the Soviet Union. The development of

nuclear weapons is also related to the development of nuclear

delivery systems (planes, short-range, long-range and

intercontinental ballistic missiles – ICBMs) and the international

community is involved in monitoring this situation, particularly

regarding developments in this sector in Iran and North Korea.

Arguments

in favour of keeping nuclear arms (the Devil’s advocate!)

(1)

They, more than the UN, have prevented a Third World War for more

than 65 years. There have been many conflicts, but none of them have

been global. Without nuclear arms the US and USSR might have gone to

war at some point during the Cold War . So their elimination might

actually lead to more

wars and make a general global conflict more

likely.

They have only been used once, by the US on Japan, to end a war, not

to start one. This is a strong argument.

(2)

No conventional war since 1945 has ever escalated into a nuclear war.

(3)

Reductions in or the elimination of these weapons must be coordinated

with reductions in other types of WMDs, or countries will

invest in those alternative weapons and the real danger to the world

may be increased, e.g. a race to develop and build biological

weapons.

(4)

If major powers reduce the number of nuclear weapons they have then

they will probably massively

increase their spending on conventional

weapons

to compensate for this. Some historians argue that World War I

demonstrated that a build-up of conventional weapons can lead to

growing tensions and war.

(5)

Nuclear weapons guarantee a country nuclear attack. So far this has

been true.

(6)

Nuclear weapons guarantee a country and a country’s allies against

conventional attacks or invasion. This is not true. Argentina invaded

the Falklands, confident that Britain would not respond with nuclear

weapons. North Vietnam and the Viet Cong defeated the South

Vietnamese government and US forces. Afghan rebels fought and

defeated the Russians and the Russian-backed Afghan government. They

were not intimidated by the strength of the US and USSR as nuclear

powers.

(7)

Nuclear weapons can be effectively used to threaten a non-nuclear

country. This does not really seem to be true. Only North Korea has

tried to use this tactic, against South Korea, and largely without

success. The US, the USSR (Russia today), France, Britain, China,

India, Pakistan – none

of them has ever done this.

Israel does not admit publicly that it has nuclear weapons and has

fought a series of conventional wars with its neighbours. It has

never threatened the use of nuclear weapons. It has threatened

conventional

bombing of Iranian nuclear research and development sites if the

Iranians continued with their program.

(8)

Prestige – This is a much-quoted but possibly mistaken idea. A

country or government may, of course, believe

that it will acquire status and prestige by developing nuclear

weapons but this is probably an illusion as the following

considerations suggest. Have North Korea and Pakistan really

acquired international prestige or become regional leaders? Don’t

Germany, Japan and Brazil have considerably more prestige because of

their economic importance? Did China and India gain prestige

internationally when they acquired nuclear weapons or when their

economies expanded to their current levels? Does the prestige of the

EU in international relations depend on French (and British? Post

Brexit?) nuclear weapons ( or NATO forces and US weapons) or on its

economic importance as a single developed market, democratic

traditions and cultural influence? Do the Arabs respect Israel more

because it has nuclear weapons?

(9)

Nuclear technology is old, no longer complex (with the right fissile

material you could built one at a US university physics department)

and you cannot turn the clock backwards. You cannot get rid of

knowledge. So should we try to eliminate them completely, or reduce

their numbers and try to improve their safety, prevent their

proliferation where this is possible, but accept that they are here

to stay?

Nuclear

technology for the peaceful production of energy

http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/france.aspx

Germany

has 7, producing 11.6% of its electrical power (compared

to 22.4% in 2010 and 17 nuclear plants)

but plans to phase out nuclear power by

2022.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_power_in_Germany

http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/germany.aspx

The

USA

has 99, producing 19.3% of its electrical power. As

of 2018, there were 2 new reactors under

construction.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_power_in_the_United_States

Japan

has 42 operable nuclear power stations (but only are 9 operating in

February 2019) producing 6.2% of its electrical power. Prior

to the earthquake

and tsunami of March 2011

Japan had generated 30% of its electrical power from nuclear

reactors and planned to increase that share to 40%. After the

disaster, all its 50 reactors were closed.

Currently

42 reactors are operable and potentially able to restart. 9 have been

restarted and a further 21 reactors are in the process of restart

approval.

http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/japan-nuclear-power.aspx

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_power_phase-out

The

UK has 15, producing 21% of its electrical power (and 2 under

construction).

http://network.bellona.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2017/05/2017-Russian-nuclear-power-NO-ISBN.pdf

http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-o-s/russia-nuclear-power.aspx

The

Chernobyl disaster was a nuclear

accident

that occurred in April 1986 at the Chernobyl

Nuclear Power Plant

in Ukraine,

which was under the direct jurisdiction of the central authorities in

Moscow.

An explosion and fire released large quantities of radioactive

material into the atmosphere. It is widely considered to have been

the worst nuclear

power

plant accident in history. Highly

radioactive fallout

entered and contaminated the atmosphere and drifted over large parts

of the western Soviet

Union

and Europe

(large parts of Germany were covered with radioactive

contamination).

From 1986 to 2000, 350,400 people were evacuated and resettled from

the most severely contaminated areas of Belarus,

Russia,

and Ukraine.

According to official post-Soviet data about 60% of the fallout

landed in Belarus.

The accident raised concerns about the safety

of Russian nuclear technology, as well as the dangers of nuclear

power plant engineering in general and human error. Russia, Ukraine,

and Belarus have been burdened with the continuing and substantial

decontamination

and health care costs of the Chernobyl accident. According to a

report by the International Atomic Energy Agency estimates of the

number of deaths potentially resulting from the accident vary

enormously: Thirty

one deaths are directly attributed to the accident,

all among the reactor staff and emergency workers. An UNSCEAR

report places the total confirmed deaths from radiation at 64 as of

2008. The World

Health Organization

(WHO) estimates that the death toll could reach 4,000 civilian

deaths, a figure which does not include military clean-up worker

casualties. The Union

of Concerned Scientists

estimate that for the broader population there will be 50,000 excess

cancer cases resulting in 25,000 excess cancer deaths. The 2006 TORCH

report

predicted 30,000 to 60,000 cancer deaths as a result of Chernobyl

fallout.

A

Greenpeace

report puts this figure at 200,000 or more. A Russian publication,

Chernobyl,

concludes that 985,000 premature cancer deaths occurred worldwide

between 1986 and 2004 as a result of radioactive contamination from

Chernobyl. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chernobyl_disaster

The

events following the

failure of cooling systems at the Fukushima

Daiichi I Nuclear Power Plant

in Japan on March 11, 2011demonstrate

that even

with great advances in the safety of nuclear technology,

exceptional events (in this case an earthquake and a tsunami) make

100% safety impossible and raise questions about the industry’s

confident claims to operate within acceptable margins of

safety.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fukushima_Daiichi_Nuclear_Power_Plant

http://abcnews.go.com/topics/news/fukushima-nuclear-power-plant.htm

http://fukushimaupdate.com/

Many

countries had already decided not to use or to phase out nuclear

power:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_power_phase-out

after

the Fukushima disaster other countries now plan to reduce or

eliminate nuclear

power:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_power_in_Germany

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/sep/14/japan-end-nuclear-power

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2011/11/27/post-fukushima-nuclear-power-changes-latitudes.html

http://nuclearstreet.com/nuclear_power_industry_news/b/nuclear_power_news/archive/2011/11/04/mexico_1920_s-energy-plans-swap-nuclear-for-natural-gas-110401.aspx

The

production of nuclear energy produces radioactive waste materials

that need to be stored on a long-term basis (for centuries). The

French nuclear power industry’s claims that a very high percentage

of this material can be recycled is widely disputed. Moreover, this

is not what is happening in most countries at the moment. So this

material also represents a threat to life. For example, experts argue

that in the US alone, 70 years after the Manhattan project began,

there are now 99 nuclear reactors and 90,000 metric tons of nuclear

waste (the product of both the commercial and defence nuclear

reactors) at 80 sites in 35 states in temporary(!) storage facilities

with no permanent storage arrangements.

http://www.nytimes.com/cwire/2009/05/18/18climatewire-is-the-solution-to-the-us-nuclear-waste-prob-12208.html?pagewanted=all

http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ieer-french-style-nuclear-reprocessing-will-not-solve-us-nuclear-waste-problems-90233522.html

http://spectrum.ieee.org/energy/nuclear/nuclear-wasteland

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/blog/2011/apr/04/fear-nuclear-power-fukushima-risks

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dual-use_technology

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thorium_fuel_cycle

The

argument for maintaining the existing power plants, at least in the

short term, is that fossil fuel alternatives are limited (but with

average oil prices in 2019 not being particularly high and additional

shale gas and oil reserves this argument now seems weak) and

polluting (contributing to climate change) and that alternative clean

renewable energy sources are only in their infancy and cannot

offer adequate supplies at the moment.

Opponents argue that renewable, green energy sources are becoming

competitive and that, anyway, this argument only underlines the need

for greater investment in renewables in order to produce a

technological revolution and lower costs dramatically. Supporters of

nuclear power also argue that the two major accidents which happened

were in Soviet Russia, using poor technology and under a government

system that was well-known for its inefficiency, and in Japan, in an

area where a nuclear power plant should never have been built because

of seismic risks. Moreover, advocates of nuclear energy claim that

more people die, directly or indirectly, in the coal-mining industry

and oil industry than die in the nuclear industry and statistics from

the International Energy Agency seem to confirm

this:

http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20928053.600-fossil-fuels-are-far-deadlier-than-nuclear-power.html#.UvlL-fvrVbg

However, there are several arguments for closing these power

stations. First, there is the danger of an accident like the ones

described above. Moreover, in Europe the EU (and UK after Brexit?)

clearly needs to adopt a common

policy since

the effects of an accident in France could easily spread to Italy,

Spain, the UK, Belgium, Switzerland and Germany. Secondly, closing

them will force countries to invest heavily and rapidly in

alternative renewable energy sources. Thirdly, they are potentially

vulnerable targets for terrorists , e.g. an attack on a nuclear

facility could lead to a nuclear disaster (e.g. by using a plane), or

a raid to acquire nuclear materials or waste (or simply the purchase

of these materials from corrupt officials) for the construction of a

‘dirty’(or ‘suitcase’) bomb for a terrorist attack (using

conventional explosives to release radioactive material into the

atmosphere). The fewer the nuclear plants the less nuclear material

there is to protect.

http://www.nci.org/nci-nt.htm

The

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is the international

organization which is responsible for promoting the peaceful

use of nuclear

energy,

and trying to prevent its development and use for any military

purpose, including nuclear

weapons.

The IAEA was established as an autonomous organization in 1957 but

reports to both the UN General

Assembly

and

Security Council . As

the IAEA points out there is no simple clear line between nuclear

energy for peaceful purposes and nuclear energy for military

purposes. So preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons in a

world in which nuclear energy is widely used for energy production is

becoming an extremely difficult, if not impossible, task.

Nuclear

weapons today

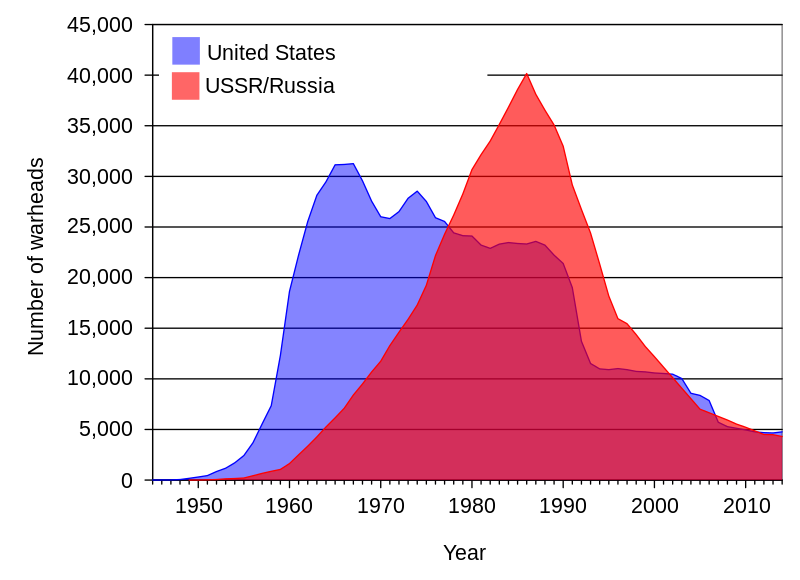

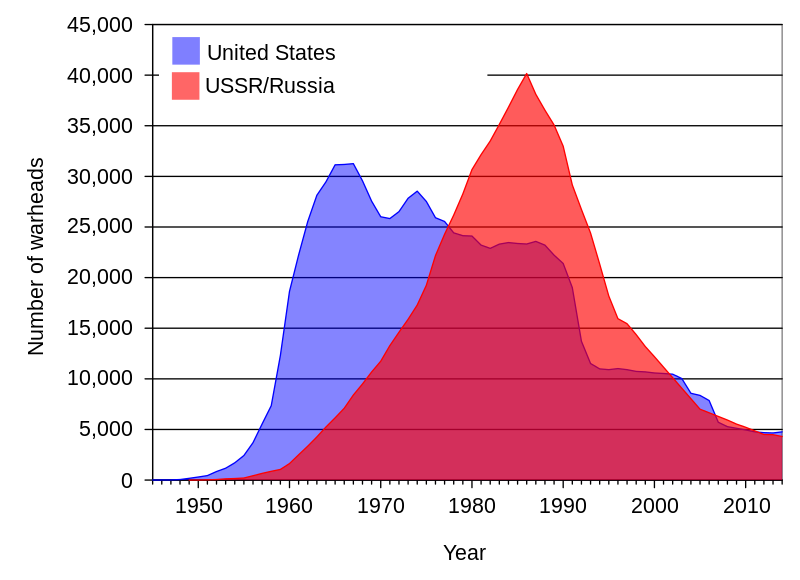

The

US and the Russian Federation made large reductions in their nuclear

arsenals through a negotiation process which began with the START 1

treaty in 1991 (also START 2, START 3, SORT) and say they are

committed to continuing this process (the New START treaty was

ratified in January 2011). From

a high of 65,000 active weapons in 1985, there are now estimated to

be some 4,120 active nuclear warheads and some 14,930 total nuclear

warheads in the world in 2015.The

US has reduced from 32,000 (active and stockpiled) at the highest

point in 1966 to 1,800

(active warheads) and 6,800 (total inventory including reserves and

stockpiles)

The

USSR/Russian

Federation has reduced from 45,000 (active and stockpiled) at the

highest point in 1988 to 1,950

(active) and 7,000 (total inventory).

|

Status

of World Nuclear Forces 2019*

|

|

Country

|

Deployed

Strategic

|

Deployed

Nonstrategic

|

Reserve/

Nondeployed

|

Military

Stockpilea

|

Total

Inventoryb

|

|

Russia

|

1,600c

|

0d

|

2,730e

|

4,330

|

6,500f

|

|

United

States

|

1,600g

|

150h

|

2,050i

|

3,800j

|

6,185k

|

|

France

|

280l

|

n.a.

|

20l

|

300

|

300

|

|

China

|

0m

|

?

|

290

|

290

|

290m

|

|

United

Kingdom

|

120n

|

n.a.

|

95

|

215

|

215n

|

|

Israel

|

0

|

n.a.

|

80

|

80

|

80o

|

|

Pakistan

|

0

|

n.a.

|

140-150

|

140-150

|

140-150p

|

|

India

|

0

|

n.a.

|

130-140

|

130-140

|

130-140q

|

|

North

Korea

|

0

|

n.a.

|

?

|

20-30

|

20-30r

|

|

Total:s

|

~3,600

|

~150

|

~5,555

|

~9,330

|

~13,890

|

Globally,

the number of nuclear weapons is declining, but the pace of

reduction is slowing compared with the past 25 years. The United

States, Russia, and the United Kingdom are reducing their overall

warhead inventories, France and Israel have relatively stable

inventories, while China, Pakistan, India, and North Korea are

increasing their warhead inventories.

All

the nuclear weapon states continue to modernize their remaining

nuclear forces, adding new types, increasing the role they serve, and

appear committed to retaining nuclear weapons for the indefinite

future. For an overview of global modernization programs, see our

contribution to the SIPRI Yearbook.

Individual country profiles are available from the FAS

Nuclear Notebook.

The

exact number of nuclear weapons in each country’s possession is a

closely held national secret. Yet the degree of secrecy varies

considerably from country to count. Between 2010 and 2018, the United

disclosed its total stockpile size, but in 2019 the Trump

administration stopped

that practice.

Despite such limitations, however, publicly available information,

careful analysis of historical records, and occasional leaks make it

possible to make best estimates about the size and composition of the

national nuclear weapon stockpiles.

“Since

1991, the United States [claims that it] has destroyed about 90

percent of its non-strategic nuclear weapons and devalued them in its

military posture. However, the Obama administration reaffirmed the

importance of retaining some non-strategic nuclear weapons to extend

a nuclear deterrent to allies. And the U.S. Congress has made further

reductions in U.S. nuclear weapons conditioned on reducing the

“disparity” in Russian non-strategic nuclear forces.

Russia

says it has destroyed 75 percent of its Cold War stockpile of

non-strategic nuclear weapons, but insists that at least some of the

remaining weapons are needed to counter NATO’s conventional

superiority and to defend its border with China. Following a meeting

of the NATO-Russia Council on April 19, 2012, Russian Foreign

Minister Sergey Lavrov stated: “Unlike Russian non-strategic

nuclear weapons, U.S. weapons are deployed outside the country,”

and added that “before talks on the matter could begin, the

positions of both sides should be considered on an equal basis.”

The

US withdrew from the ABM Treaty (1972) in 2002 (which banned the

development of a missile defence system).

At

the November 2010 NATO Summit in Lisbon, NATO’s leaders decided to

develop a ballistic missile

defence (BMD)

capability to pursue its core task of collective defence

and specifically against an attack with missiles. Despite NATO’s

initial attempts to reach agreement with the Russian Federation,

Russia has made its opposition to the plan clear. (Moreover, many

technical experts doubt that such a system will ever be 100%

effective, which is the only level of safety worth having if the

missiles have nuclear warheads.) This and the situation in Ukraine

raised tensions with Russia and put at risks the prospects for

further cooperation between the US and Russia on nuclear arms

reductions.

In

October 2018 President Donald Trump said the US will withdraw from

the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty claiming that

Russia had violated it. The

deal banned ground-launched medium-range missiles, with a range of

between 500 and 5,500km (310-3,400 miles. e.g. Moscow to Paris).

There are concerns that without a new understanding between the US

and Russia we could now see the unravelling of all the progress made

in the last 25 years and a new nuclear arms race.

Worsening

relations between the US, NATO and the Russian Federation (due to

events in Ukraine, sanctions, the NATO missile defense system and the

US suspension of the Intermediate-Range

Nuclear Forces Treaty)

seem to make future negotiations and progress on further reductions

unlikely.

The

situation in November 2019 seemed blocked:

Both

sides now seem to be set on a new nuclear arms race.

In

contrast, former US President Obama had talked about the need for an

international commitment to eliminate nuclear arms completely.

Realistically, this is unlikely to happen in the near future, without

the prospect of some kind of world government. Some experts even

doubt the advisability of such a development.

However,

there is general consensus in the global community that the number

and types of nuclear weapons needs to be reduced and further

proliferation avoided if possible.

There

is less consensus on the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes,

but general agreement on the need for:

1)

More integrated strategies for monitoring and responding to the

recruitment of trained nuclear scientists and engineers by suspicious

parties, and against the purchase or acquisition of fissile

materials, nuclear waste materials, nuclear know-how and technical

expertise (Pakistani scientists in North Korea and Iran), non-

nuclear components of a nuclear bomb or advanced delivery systems by

such parties on the black market.

2)

increased secret service surveillance and international cooperation

in this field.

3)

improvements in the security provided to and at nuclear plants.

4)

better and more regular tests on the safety of nuclear facilities.

5)

better and permanent arrangements for the recycling and/or storage of

nuclear waste.

For

source material about the dispute between the UN, US and Iran see:

Background

US

and Russia